It also taught me a lot about the destructive power of shame in medicine.

I was about to go on stage and admit that I was not perfect.

In the basement of the Huntington theater, I didn't feel like eating the sandwiches the staff had kindly laid out, but I nibbled on one anyway. I fiddled with my hair and makeup, trying to remember how concealer worked after several years of giving up on it. I tried to remember the words to my story, a story I had rewritten more than anything else I had ever written. I tried to tell myself that it would be OK to walk onto that stage, in front of a thousand people (including dozens of loved ones), and tell them that I had failed as a doctor.

"The only way to be a good doctor is to be a perfect doctor."

This message may never be spoken, but it is implied at every step of our training and practice, even from the time we are crafting college applications at 16 year olds. The pressure only intensifies when real harm is on the line. The encouraged response is to study harder, sleep less, and never admit fear.

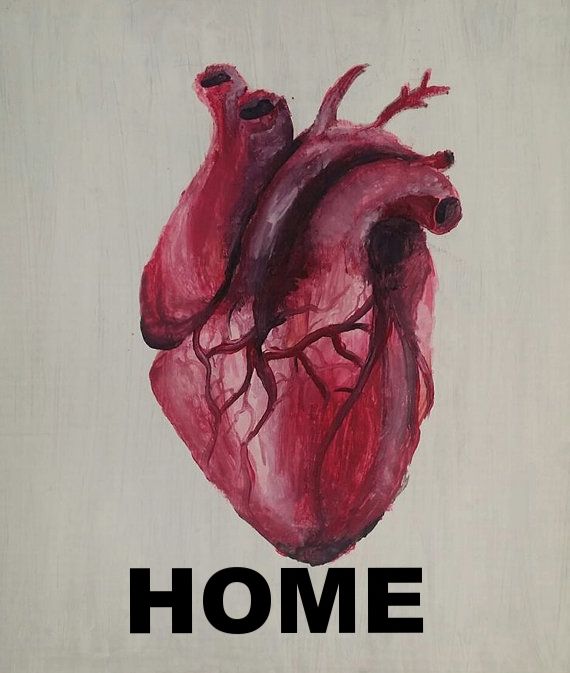

I won a Moth story slam telling a story about a good friend, Nina, who opened her heart to me. The story I decided to tell at the Moth was a story that would require me to open mine, on stage. I considered backing out many times. But I felt that I had a responsibility to the patient I had failed, to other physicians struggling with this kind of shame, to a medical culture that tries so hard to pretend that physicians are not human, with devastating consequences.

This episode has replayed in my mind every time I felt I had fallen short, and I thought I understood it. I did not anticipate how it would feel to relive one of my most shameful episodes over and over through the writing process. I cried to more than one friend who suggested this might be too raw to share, even three years after the fact.

The Moth (and maybe all great storytelling) demands that stories be personal and specific. But making mistakes, confronting shame, and being humbled in the face of our failures is not just my story. This is the story of physicians around the world, who believe the lie they are told: the only way to be a good doctor, is to be a perfect doctor. Some believe it so strongly they take their own lives rather than face their failures.

I knew I had to tell my story, because it was our story. If I couldn't, how could I ask others to do the same?

After dozens of revisions, I came to the sweetest reward writing has to offer: bringing meaning to the painful experiences of our lives. I can't undo the harm I caused. I can't go back and say exactly the right thing, be the kind of doctor I wish I had been. But I can honor my patients by admitting my mistakes and continuing to grow.

The story I tell is of a man I call Tom. His loss continues to weigh on me. What I did not expect, though, was that when I allowed myself compassion for falling short, other moments of our relationship came back to me: the way he spoke of his family, his work, his travels and his curiosity. Tom was a man who always showed up for those who needed him and made the best out of his opportunities. He was a deeply grateful man. Not understanding why he died, why I couldn't stop it, overshadowed other memories of him, memories I got back when I forgave myself.

Getting onto the stage with a thousand people in the audience was harder than I thought it would be. It helped that I had so many loved ones in the room. It helped even more that I knew so many in the audience had their own episodes of shame that they carried, and were looking for a way to put them down.

To be told for so many years that mistakes are unacceptable, even as you are sleep deprived, asked to do more and more tasks, hungry, and isolated, is to learn you are unworthy of forgiveness, especially from yourself. It is to be hobbled when trying to imagine a whole system that could be better and safer, because you are consumed with the ways that you have to be better, and ignore the things that set you up for success or failure.

A system that only works when doctors and other providers perform at a superhuman level is a system that endangers us all. It is a system that robs us of our reasons for being here in the first place, that promotes the slow creep of cynicism and destroys flexible minds. Our wounds make us who we are. It is time to shatter the lie that perfection should be our goal.

The warmth of the people in the theater that night, especially my family, my friends, and my cherished fellow residents, overwhelms me. I didn't anticipate that I would speak to people after, patients and providers, who related to my story and shared their own. If this story touches you, please share it with students, friends, or colleagues that you think need to hear it.

I am not perfect. I am wounded. And it has made me so much more than I could have imagined.

What do others have to say about the culture of shame in medicine? Click to find out what people said on Twitter.